Making A Capital Investment : How The British Created New Delhi

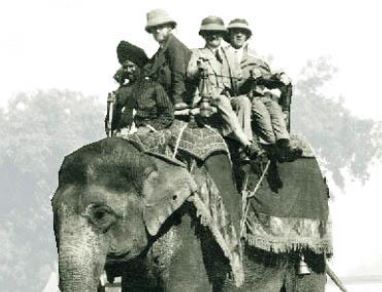

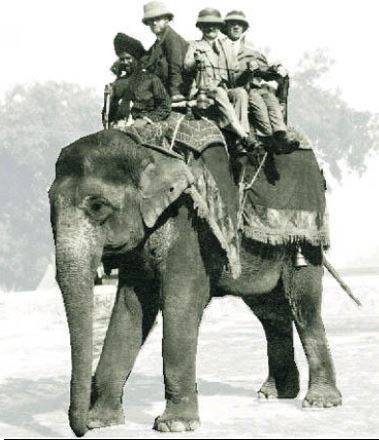

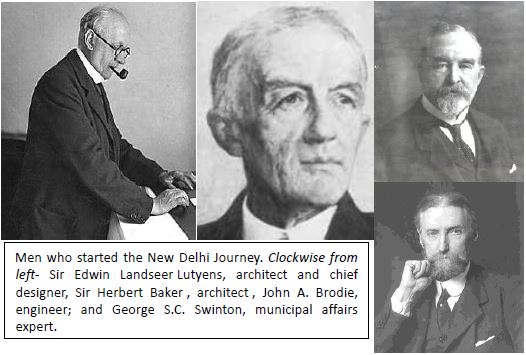

Members of the Town Planning Committee tasked to plan the new city of Delhi : Sir Herbert Baker, Sir Edwin Lutyens and George S. C. Swinton, ride along Raisina Hill atop an elephant surveying for a suitable place to locate Imperial Delhi

Back in 2013, the then Delhi Government had given a new tagline for Delhi - Dildaar Delhi (magnanimous Delhi). It was quite apt, for Delhi has over centuries embraced the pauper and the king, poets and the worldly men, saints and the capitalists. Delhi has seen eight cities, the most contemporary being the one built by the British. The Imperial Delhi later rechristened New Delhi left the footprint of British architecture amongst the large number of architectural styles the city has witnessed.

Poet Mir Taqi Mir, probably said the best lines about Delhi, while he pined about the city after migrating to Lucknow following the sack of Delhi by Ahmad Shah Abdali

दिल्ली जो एक शहर था आलम में इंतेखाब

रहते थे वही जनाब रोजगार के

जिसको फलक ने लूट कर वीरान कर दिया

हम रहने वाले हैं उसी उजरे दयार के

This article traces the story of the building of the new capital of British India. This article has been written by Sudipto Sengupta and researched by Amit Mukherjee.

The crown was studded with 6,170 diamonds and had sapphires, emeralds and rubies sewn onto a velvet miniver cap. Designed by the Crown jewellers- Garrad & Co in London, it weighed around 34 oz or 2 lb. The King remarked that upon wearing the weight of the crown gave him a headache.

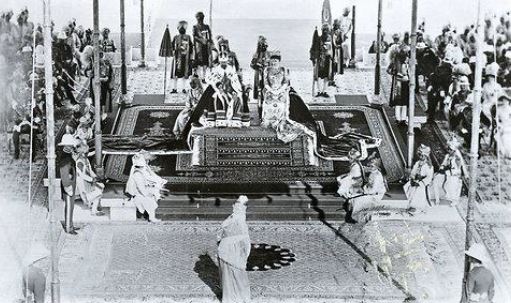

The King was George V and the Imperial Crown of India had been designed for the occasion of the Delhi Durbar held in 1911 to commemorate the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary and felicitate their proclamation as Emperor and Empress of India.

Lord Hardinge, the Governor General of India, and host of the Delhi Durbar had a headache of a different kind. He had to find a ‘Grand Gesture’ or a ‘boon’ which was expected of the King Emperor at the Durbar by his subjects in India on this occasion. That gesture had to be significant enough to behove the emperor of the British Empire, something which would be remembered by generations to come.

Political circumstances during the time provided the opportunity for the “grand gesture”. Bengal was in turmoil due to its partition in 1905, Britain was hard pressed to contain the agitation. Hardinge summarized the ground situation thus “the political power of the Bengalis has not been broken …. they will never cease to agitate until they have obtained a modification of the partition”. Hardinge sketched his ‘Grand Gesture’ plan on the back of this rather difficult political situation. In the Delhi Durbar, King George V would revoke the partition of Bengal and thus be seen as a benevolent monarch , and concurrently announce shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, demonstrating that absolute power of India’s destiny remained with His Majesty. The declaration of a new capital city was to the Emperor’s ‘ Grand Gesture’.

On Tuesday, December 12, 1911, the Delhi Durbar assembled at Coronation Park in Delhi. In attendance were 90000 people including the British bureaucracy and 562 rulers of Indian princely states. The King George V was heralded with the sound of trumpets and the roll of drums as he climbed the stage to make various benevolant royal announcements- money for education, enhancement in salaries for the Government employees, reprieve to prisoners etc. However there was no word on the capital shifting. After the announcements and much clapping the King stepped down from the dais. Suddenly as if as an afterthought or probably for effect, His Majesty climbed back on the dais and declared that the British Government after much thought and deliberation had decided to transfer the seat of power from Calcutta to Delhi.

The political map of India had suddenly been altered - this was the ‘Grand Gesture’ from the King which Hardinge had engineered. Copies of gazette on the declaration printed secretly beforehand were distributed which made the pronouncement a statute. On 15 December 1911, King Henry V and Queen Mary laid the foundation stones of Imperial Delhi where now stands the physics department of the University of Delhi. A year later these stones were shifted 11 kms away to Raisina hill where the Viceroy House (present Rashtrapati Bhavan) and the Secretariat (present North and South Block) were built

The Sovereign made it clear at the foundation stone laying ceremony that no effort be spared to make a splendid city. Given the number of great buildings of the Mughals and beyond strewn across Delhi, the British were determined their capital must “quietly dominate them all”. Conveying the King’s sentiments to Secretary of State for India, Lord Crewe, Lord Stamfordham , King’s Private Secretary wrote, “we must now let him [the Indian] see for the first time, the power of western science, art, and civilization.” The new capital is to stand as the motif of British Superiority”.

| The forgotten foundation stones of Delhi

The foundation stones of New Delhi laid by King George V and Queen Mary on December 15, 1911 - lie forgotten within locked chambers in North and South Block. These halls, known as Yaadgaar chambers, are located at identical places in North and South Blocks. The foundation stones of New Delhi, two in number, were originally laid by the British king and queen at a spot where the Delhi University’s north campus now stands. The stones are simple blocks of white sandstone with just a date - 15th December 1911 - engraved on it. The plain looks reflect the hurry in which the stones were made ready. After the King took the empire by surprise on December 12, 1911, announcing the shifting of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi, officials had just three days to prepare the stones. According to newspaper accounts of the time, the original site of the stones was “700 feet southwest of the flagstaff tower on the Ridge”, which would put it close to the western end of where the physics department of Delhi University now stands (the exact spot hasn’t been preserved and is thus unknown). The ‘first stone’ of the new city was laid by the king and the ‘second stone’ by the queen in a hurriedly organized ceremony attended by just a handful of officials and princes. When the site of the new capital was finalized - and it happened to be in the south of the walled city and not where the ‘foundation’ was laid - the stones were shifted to their present location on July 31, 1915. According to the marble inscription on the dome of each chamber, the stones were placed in this first public building of the imperial city in the presence of Viceroy Hardinge. The stone originally laid by King George is in South Block while the one laid by the queen is in North Block. The Yaadgar chambers are not open to public. |

With the intent clear, now came the time to select the men who would translate the grand vision on the ground. This was to be done by the Town Planning Committee, which however did not get a smooth start. The first shortlist of the committee had three members- Deputy Commissioner of Punjab, the Superintending Engineer of the Jamuna Canal and the Consulting Architect to the Government of Bombay. These names were struck down by Sir John Fleetwood Wilson, a senior member of the Viceroy’s Council with the noting that the proposed panel comprised of ‘non entities’ and that best available talent had to be put on the job if the Sovereign’s desire for the finest city of the British Empire was to be translated on the ground.

Search for three names with the requisite talent, track record and stature was started, finally zeroing on three member team - Edwin l. Lutyens, architect; John A. Brodie, engineer; and George S.C. Swinton, municipal affairs expert. There was another exceptional architect who was in the race- Henry Vaughan Lancaster, but lost out to Lutyens, not on technical skills but on the consideration that Lancaster was rather “brusque and irritable”. Lancaster missed immortality by a whisker, and the epithet “Lutyen’s Delhi” might well would have been Lancaster’s Delhi”, only if Lancaster been a bit mild mannered. And of course had Lord John Wilson not objected to the initial panel of names, New Delhi as we know it today might have never fructified.

On 12 March 1912, the King gave his approval to the names and on the side margin of the proposal noted “excellent”. Before leaving for India, the trio had a meeting with the King at Buckingham palace where the King told the Delhi design team that the site where the foundation stone he and the queen had laid the previous year was not sacrosanct and that the ridge area with its monuments was to be considered as sacred.

The “Delhi Experts” set sail for India on 28 March 1912 with a heavy expectation and responsibility on their hands. With the writ of the Sovereign in place, and the team to design the city now in India, the next challenge was where to find the site for the new city. There were certain considerations- health, security, room for expansion, cost, water supply and drainage, electricity and transport as well as the relationship of the new city to Old Delhi and the cantonments. This was a tall order` to ask in a city which had more than 2000 years of history behind it.

The search for the site was an agonising process, the Delhi Expert committee scoured through the landscape both on the North and South of Sahajenabad in Ford Landauletter or De Dion cars and even on elephant. The gruelling heat and the sparse landscape provided not only distress but also encounter with wild animals and frayed tempers amongst the committee members. The cups of tea and cold bath at Hotel Maidens and ofcourse the scotch helped cool matters.

However despite its exertions the Delhi Expert Committee could not decide on the site, and Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy took upon himself to get the site finalised. He wrote in his book The Indian Years, “I, then, after rejecting the Malcha site, mounted and asked Hailey [later Lord Hailey, then Commissioner of Delhi] to accompany me to choose a new site, and we galloped across the plain to a hill some distance away. From the top of the hill there was a magnificent view embracing old Delhi and all the principal monuments situated outside the town, the Jamuna winding its way like a silver streak in the foreground at a little distance. I said at once to Hailey, ‘this is the site for government house,’ and he readily agreed.” The site which took Harding’s fancy was the Raisina Hill. The Viceroy’s House [now Rashtrapati Bhawan] and the Secretariat buildings [The North Block and the South Block] were to be located atop the Raisina Hill.

The task Lutyen’s was asked to do was not easy. The Times of London in October 1912 said it well ‘What (Moghul Emperor) Akbar sought as an individual, we have sought as a race – the union of new principles with what is best in the old. Let us leave, like him, an architecture that truly embodies that ideal.’ The expectation of making one of the finest cities in British Empire would have made any architect nervous. Edwin Lutyens the chief designer and architect thought it appropriate to co-opt his friend Herbert Baker, a friendship which started when the two apprenticed with the same architectural firm in London. Baker then in South Africa on an invitation from Lutyens, agreed to come to India and be part of the Delhi Town Planning Committee. However, the two would in due course, as we will see later in this article were to fall apart.

With the location of the new city now decided, the architectural style had to be finalised. Political considerations had to be weighed against the creative freedom of the architect. Viceroy Hardinge favoured a mix of oriental with the western architectural style, but the Viceroy was not having an easy time clearly defining this concept. Robert Irving describes the Viceroy’s uncertainties in his book Indian Summer, “western architecture in July 1912 became Italian in August, some form of Renaissance in September, and a good broad Classic style in October.”

The architects were asked to tour the forts and cities of Jaipur, Agra and as far as Mandu in present day Madhya Pradesh. It was curious as to how Lutyens and Baker would amalgamate Indian and English architecture as expected by the Viceroy. Both were essentially imperialistic in their outlook. In a letter to his wife, for example,Lutyens described Indian architecture as “essentially the building style of children.” Even the Taj Mahal, he complained, was “small but very costly beer.” However thankfully the political prejudices did not overshadow the creative instincts of the architects and they could remarkably weave in Indian architectural elements.

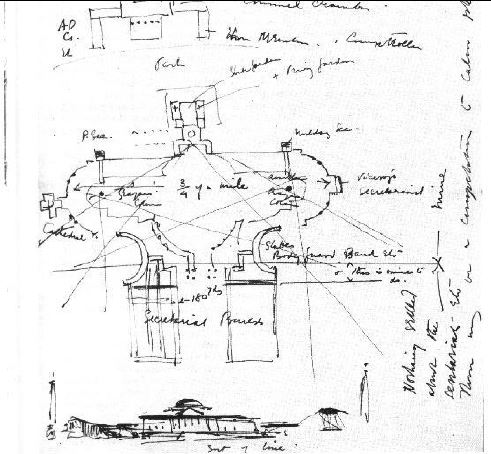

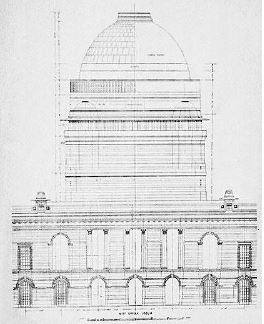

A sketch by Lutyens dated June 14, 1912 shows a plan and elevation of the Viceroy’s House (now Rashtrapati Bhawan) and associated buildings

With the site chosen, Lutyens now got to work, this was his hurrah! moment, he had been entrusted with building a brand new city, a commission most architects only dream about. Lutyens personally handled every detail of New Delhi’s planning—a city spread over an area of about 26 square kilometres for approximately 65000 people. Its plan reflects his fervor for geometric symmetry, which is expressed through sequences of triangles and hexagons. Despite Lutyens’ known insensitivity to the numerous tombs, gateways, and old structures which attest Delhi’s rich ancestry, his plan gained enormously from the use of historic structures as focal points at the end of major vistas. New Delhi would have been far less exciting without the texture and character of the relics left behind by great builders.

Lutyens’ plan is also remarkable for the generous green spaces, lawns, watercourses, flower and fruit bearing trees, and their integration with the parks developed around monuments. What emerged was one of the world’s outstanding garden cities’, not only on account of its refined emphasis on elegance and civic grace, but also because in practical terms its greening reduced temperatures during the hot, dusty summer months of northern India.

With the layout in place, it was now time to design the showpiece of the new city, the central vista comprising of the Viceroy house (Rashtrapati Bhawan) and the Secretariat (North Block and South Block). It was placing of these buildings which lead to huge acrimony between Baker and Lutyens. Lutyens wanted Government House to stand on top of Raisina Hill so that it would dominate an otherwise flat landscape. But Baker’s Secretariats, originally meant to stand at the hill’s bottom, got in the way. Inspired by the achievements of other imperial authorities – the Greeks, Romans and Mughals – both saw the building of New Delhi as heralding a new architectural era. Raisina Hill, a rare elevated hotspot, is where the flagship buildings of imperial authorities would stand – and both wanted to leave their mark there.

This is the view which lead to acrimony between once friends Lutyens and Baker. Only the dome of the Rashtrapati Bhawan is visible, the rest of the building is hidden by the gradient of the road and the North Block and the South Block.

Lutyens agreed to make space for the two Secretariats (North and South Block) on the hill only to bitterly regret it. To make space for them, Viceroy’s residence (present Rashtrapati Bhawan) had to be pushed further back from the edge of the hill. Only later did he realizet that the plan he agreed to would make it impossible for anything but the dome of Government House to be visible from below. He blamed Baker, who designed the road linking the Secretariats, for miscalculating the gradient. Lutyens was right: if you walk from India Gate down Rajpath you’ll notice that Rashtrapati Bhavan gradually sinks behind the hill.

Lutyens tried to persuade Baker to change his plans but to no avail. In his letter to Baker, Lutyens said “a colossal artistic blunder has been made, and future generations will, I am convinced, recognize this and condemn its perpetrator.” Baker’s defence centered on technicalities, on the fact the Lutyens himself had approved of the plan. Lutyens called this his “Bakerloo”.

While neither was a fan of Indian architecture, both wanted a blend of Indian and Western elements for New Delhi. The North and the South Blocks which are Baker buildings are essentially European with an Indian accent. He used classical European forms, like colonnades and renaissance- like domes, and Indian decorations, like arched porches and lattice screens. Lutyens, on the other hand, was more committed to a substantial fusion of styles. The result was forms that stood out for their originality. His crowning achievement is the great dome of Rashtrapati Bhavan, partly inspired by the Buddhist Stupa in Sanchi and the Pantheon in Rome. Robert Byron, the famous British travel writer and one of the first visitors to New Delhi after the city’s completion, in an essay praised the dome’s design for its “individuality, its difference from every dome since the Pantheon.”

Despite differences Baker recognized Lutyens’ superior talent. In a eulogy written for Lutyens after his death in 1944, he argued that “in his talent for artistic rather than constructive design he may be considered even greater than Wren (who at the time was widely seen as the greatest British architect of all time)”. Baker also gave a lucid analysis of his stormy friendship with Lutyens:“Looking back after these many years…. I can see more clearly that our personal differences had their roots in our natures and outlook on art. He concentrated his extraordinary powers and intellectual values to the sacrifice sometimes, I considered, of human and national sentiment and its expression in our buildings.”. Today, despite their differences, Lutyens’s and Baker’s buildings rise atop Raisina Hill as part of a cream and red-sandstone whole that stands as the greatest architectural legacy left by the British in India.

While the Viceroy’s House and the secretariat buildings flanking the Central Vista were being built (from 1914 till their completion in 1931) amid mounting acrimony and disagreement between its chief builders — Edward Lutyens and Herbert Baker — a clutch of other buildings were designed and swiftly executed by the Chief Architect to the Government of India, the relatively lesser known, R.T. Russel and his subordinates. It was Russel who built the commercial hub of Delhi — the Connaught Place in 1933 as well as the Gol Dak-khana (the Central Telegraph Office), the aerodrome, the law courts, the Flagstaff House that was later occupied by Nehru and renamed Teen Murti House, and the Eastern and Western Courts to house visiting legislators as well as approximately 4000 bungalows of different kinds meant to accommodate a small army of government minions.

E. Montague Thomas designed and built the first secretariat building of New Delhi which housed the Secretariat of the Government of India, and was built after the capital of India shifted to Delhi from Calcutta. This temporary secretariat building was constructed in a few months’ time in 1912, It functioned as the Secretariat for another decade, before the offices shifted to the Secretariat building on Raisina Hill. This building set a style for the bungalows that are today considered such a distinctive part of “Lutyens Delhi”. This building presently houses the Delhi Vidhan Sabha.

Herbert Baker, W.H. Nicholls, C.G. and F.B. Blomfield, Walter Sykes George, Arthur Gordon Shoosmith,Henry Medd and other British architects designed several public buildings meant to house hotels,banks, schools, etc. The greening of Delhi was conducted with masterly precision using P.H. Clutterbuck’s list of Indian trees. W.R. Mustoe, Director of Horticulture, ordered the planting of avenue trees and Mustoe along with Walter Sykes George landscaped and planted the garden planned by Lutyens inside the Governor’s House,a Mughal-style garden included at the insistence of Lord Hardinge.

The 1930s also saw the construction of four big schools, namely, St.Columba’s, Saint Thomas’s, Somerville and Modern schools; the swanky Imperial Hotel, the Regal cinema in the Rivoli building, a multipurpose stadium called the Irwin amphitheatre, a picturesque 27-hole golf course spread over 177 acres, and the present ECE House and the Scindia House, both built on the fringes of Connaught Place; and the Free Mason’s Hall whose foundation was laid by Lord Willington, the Viceroy and Governor General of India in 1935. Earlier, in 1930, the foundation was laid for a hospital, to be known as the Irwin Hospital( now known as Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Narain Hospital), in what was till then the Central Jail complex. The Irwin College for women was established in the same year and later, the Willingdon Hospital(Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital).

|

Unsung Contributors to Building of New Delhi It is not fair to give all credit to Lutyens for making of New Delhi. There were others with similar talent and vision who contributed to making of the new city. Robert Tor Russell built Connaught Place, the Eastern and Western Courts, Teen Murti House, Safdarjung Airport, National Stadium and over 4,000 government houses. E. Montague Thomas designed and built the first secretariat building of New Delhi which set a style for the bungalows. Herbert Baker made seven bungalows and the North and South Blocks. The other bungalows of New Delhi are the work of architects like W.H. Nicholls, F.B. Blomfield, Walter Sykes George, Arthur Gordon Shoosmith and Henry Medd. Lord Hardinge insisted on roundabouts (Lutyens had initially designed the streets at right angles) to break the sweep of the hot winds, hedges and trees (Lutyens said the trees wouldn’t survive) and demanded the Raisina Hill site for the Viceroy’s House (Lutyens preferred a more southern setting closer to Malcha). Hardinge also insisted on a Mughal-style garden for Viceroy’s House (Lutyens was keen on an English garden with ‘artless’ natural planting). Using P.H. Clutterbuck’s list of Indian trees, W.R. Mustoe, director of horticulture,was actually responsible for the roadside planting work for New Delhi’s avenues. It was Mustoe and Walter Sykes George who landscaped and planted Lutyens’ Mughal Garden. Swinton Jacob, advisor on Indian materials and ornaments, suggested raising the ground level of Rashtrapati Bhavan, on a carefully studied contour plan. Sandstone as building material was suggested by the geological department, which got no credit but only received brickbats for the sandstone’s heat-retentive qualities. Lutyens was opposed to use of sandstone and even considered use of marble for the Taj unnecessary. Much later Lutyens did accept the contribution of others to the Delhi plan especially that of Lord Hardinge, he said “This new city owes its being to Lord Hardinge”. |

It took the builders of Delhi 19 years to build a modern, new capital that they were destined to rule from a mere 16 years! While the new city north and west of Shahjahanabad continued to grow into a modern metropolis and a showcase for rising western architects out to display their talent and ingenuity, the old city of Delhi disintegrated after the Durbar of 1911. No attempt was made to restore the buildings that had been destroyed or razed during the Revolt of 1857, nor was any effort expended on linking the old city with the new. An invisible cordon sanitaire divided the two: the old was cramped, diseased, decaying and poorly-serviced whereas the new was spacious, sanitised, well planned and well laid out. Pockets of abysmal neglect and wanton disregard for normal standards of health and hygiene co-existed with oasis of privilege.

The most important contractor for the construction of the iconic buildings was Sobha Singh (father of the legendary Khushwant Singh).For the South Block and War Memorial Arch (now India Gate), Sobha Singh was the sole builder. He also worked on some parts of the Viceregal House (now Rashtrapati Bhavan) and Vijay Chowk. He constructed many residential and commercial buildings, including the Connaught Place market complex, as well as the Chelmsford, A.I.F.A.C.’s Hall, Broadcasting House (All India Radio), The National Museum, Dyal Singh College, T.B. Hospital, Modern School, Deaf and Dumb School, St. Columba’s School, Red Cross Buildings and Baroda House.

The actual construction of New Delhi began after World War I. A Meo village atop Raisina Hill was shifted, the residents moved to where stands the present colony of Bhogal, across the Barapulah Nalah. Land was also acquired on the Southern side till Safdarjung Tomb for the Garden city now called Lutyens Bunglow Zone (LBZ). A circular railway line near the present day Parliament House called Imperial Delhi Railway was constructed for transporting building material and workers to the site for the next 20 years. Another railway line connecting Delhi and Agra passed through the hexagonal area where the India Gate stands. This was also shifted to a place which is the

present day New Delhi Railway Station.

In 1912 Hardinge estimated the new capital could be built in four years for £4 million. The final cost was more than £10 million. King George V announced the building of new capital city at his Delhi Durbar of 1911 and the nearly finished city was inaugurated in 1931 – “five minutes before closing time”, as Nikolaus Pevsner remarked. An apt statement - of the 200 year of British rule in India, the new city remained the capital for merely 16 years. In 1947 India won freedom, and British had to leave the city which they had built with so much care, resources, controversy and contempt for the locals.

Rich & worth reading. Studied few lines only & got a bit knowledge which reveals birth about Indian Capital. Rare collection about the Capital , New Delhi. Will share & leave detail comments after reading the complete article.

Among the benefits bequeathed by the British connection were the large scale capital investments in infrastructure, in railways, canals and irrigation works, shipping and mining; the commercialisation of agriculture with the development of a cash nexus; the establishment of an education system in English and of law and order creating suitable conditions for the growth of industry and enterprise; and the integration of India into the world economy.

By the way! The best essay writing service - https://www.easyessay.pro/